North to Alaska

Searching for Gold on the Alcan 5000

STORY | Klay Jones

Photography | Tedrick Mealy

A ragtag crew of eccentrics assembled in the parking lot of a nondescript Kirkland hotel, united by a shared sense of adventure. At first glance, the scene resembled a casual cars-and-coffee gathering, but the extra fuel tanks and rally decals hinted at the road ahead. A cluster of Avants stickers, half a dozen at least, confirmed we were in the right place.

The mix of participants was as eclectic as their vehicles: seasoned rally pros, automotive journalists, travel vloggers chasing new content, longtime friends chasing old thrills, and wide-eyed rookies like us, eager but untested.

There were groups of adventure motorcycles with aluminum panniers adorned with international flags, marking past adventures. The auto entries were diverse. A Porsche Carrera 4S with a roof-box sat next to an Audi 4000 Quattro. Daily drivers, a Swedish wagon, overland money pits, and our oxidized silver Toyota FJ cruiser filled out the pack.

The Alcan 5000 Rally traverses more than 5,000 miles of some of the most remote, beautiful, and unpredictable roads and trails in North America. The route stretched from Kirkland all the way to the Yukon, Arctic Circle, and Alaska, before looping back again. Some people came to compete, stopwatch in hand, chasing precision scoring. Others, like us, came for the scenery, the camaraderie, and the strange joy of long days on desolate roads.

The Alcan also serves as a benchmark for a challenging, rough route that will test the durability of both teams and vehicles. For that reason, automakers and equipment manufacturers see it as bragging rights and support teams with loaner cars and prototype equipment.

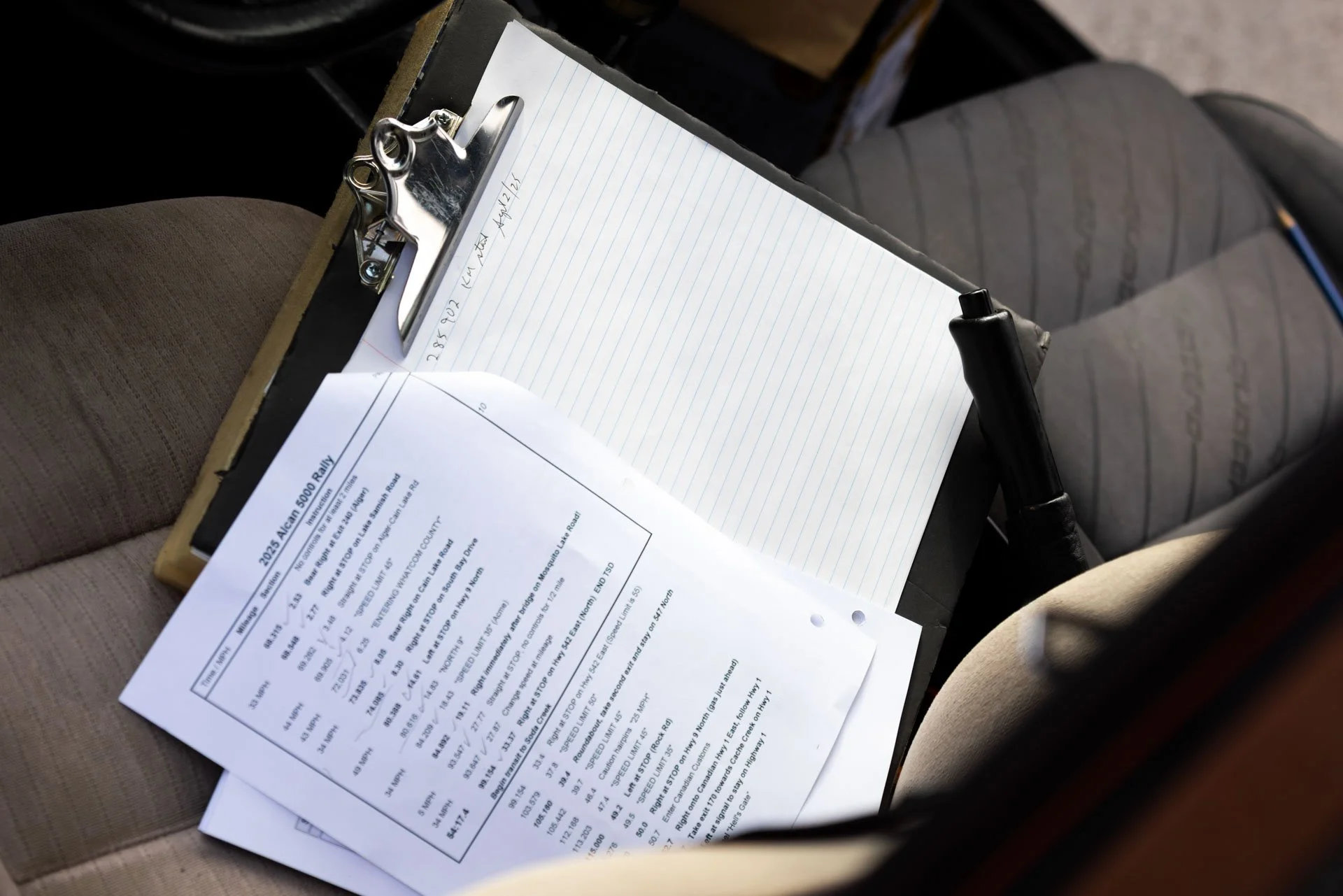

As 8 a.m. approached, the vehicles staged, waiting for their timed departure to begin the first time-speed-distance competition. Navigators read route books with scrawled section times, and motorcyclists slid abbreviated versions into their gas tank slip covers. Trunks were full of snacks, roofs sported HAM radio antennas, and odometers were reset.

North to Alaska, the rush was on.

INTO CANADA

It only took a half-hour to reach what already felt “remote” after crossing the Canadian border into British Columbia. Cities were quickly replaced with towns. We passed Hells Gate, where the Fraser River narrows into turbulent chaos. The early stages of the rally were about finding our rhythm. Gas every 150 miles, remaining constantly skeptical of the next gas station… older participants hoping their bladders had a similar range.

The Alcan wasted no time testing us, starting with fuel. The Audi Quattro fuel pump overheated and needed a pause. An hour later, the team swapped in a spare fuel pump they’d wisely packed from home. It was the first of many unscheduled stops; four hours to cover just 85 miles. By the evening, the co-driver Peter hypothesized “what if it’s a vacuum problem.” He removed the gas cap, and by god the pump stayed cool. By day’s end, the rally had already claimed its first victim, a Porsche Cayenne, but the battered Audi pressed on.

The rally kept moving north to Quesnel and Fort Nelson before entering the Yukon. We were slowly leaving summer wildfire smoke behind while detecting signs of fall.

THE ROAD NARROWS, THE LAND EXPANDS, THE WILDLIFE APPEARS

By the time we crossed into the Yukon, the sense of scale had changed. Traffic thinned with only sprinters and semis sharing the road, towns became rarer, and road construction looked more like mining operations, as crews tried to beat the first freeze.

As civilization disappeared, wildlife took its place. We spent the day coming across herds of bison, wild horses, and caribou. The temptation to be the “Instagram tourist” and get a closer shot hit us, but we resisted. Luckily, the clouds of mosquitoes we feared never materialized.

After 10 hours of driving on Day 4, we entered Whitehorse and reached another milestone… the last McDonalds and Walmart between ourselves and the Arctic Circle. We were told to be careful of gas thieves, so we were sure to double-check our spare tanks the next morning. Still full. Onwards.

Pulling out of Whitehorse, the sweeping corners were bordered by aspens and poplars that blazed gold in the morning light. The beauty wasn’t just visual. Getting out of the car, the silence was overwhelming. My ears were left ringing from road noise with no other sound present to challenge it. Wildfire smoke slowly cleared. Even gas stations were changing. Instead of tap-to-pay, we had to take photos of the numbers on the pump to show the cashiers in the log cabin general store.

In Whitehorse, an annoying whine came from the Audi’s clutch. No issue now, but for how long?

THE DEMPSTER

Day 5 was the first “long day” as we accepted a “go farther” challenge that extended our route from seven to 14 hours, taking us within striking distance of the Arctic Circle. We were approaching the Dempster Highway. After passing through Tombstone Park, we began to see the diversity behind the “rough road” warnings. Potholes, craters, trenches, frost heaves, and washboard required different evasive maneuvers. The Dempster, like the Alcan, showed no mercy. A sprinter passed us on a flatbed tow truck, with evidence that it had overturned. It was the second that day. Then came the flat tires. The Alcan teams had several, but came prepared with one, if not two, spares each. Several teams paused their adventure to help others repair their damage, including a German family with two flats on one van. Wo ist dein Ersatzreifen?

We made it to Eagle Plains, our stopping point for the night, just as fog rolled in. Our only source of gas for seven hours had a red flashing light and alarm going off. We crossed our fingers that it would be fixed by morning. Entering the motel, we were greeted by a wolf-like dog, an abundance of taxidermy, and a fugitive manhunt for The Mad Trapper of Rat River in the 1930s. Lodging this far from civilization can be quirky.

The next morning, Day 6, we made the final drive to the Arctic Circle sign. An hour of photos was quickly followed by a familiar question. “Can you follow us back to the tire shop? We have a slow leak,” asked Peter, the current points leader. We tried to keep up as they sped through the Canadian Tundra back to the Eagle Plains, only to find them stopped near a makeshift dirt airstrip. Within minutes, the jacks and impact drivers were out, and fresh rubber was on the Bronco for the long drive back to Dawson City. Peter, always the competitor, later told me these issues convinced him to skip the remaining extreme controls (dirt detours) for the first time, to maximize his chances of winning the Time-Speed-Distance (TSD) portion of the rally.

WEST TO ALASKA

Day 6 would finally take us to Alaska after 3,000 miles of anticipation. We headed to the “ferry dock” in Dawson City, which was merely a large dirt ramp pushed into the river. A small ferry from the 1960s shuttled us across the river to the Top-of-the-World highway. We drove down the spine of a road lined with fall colors on our way to the Alaska border. We arrived at a desolate customs station. With a thunk, we had a caribou customs stamp on our passports, and we were back in the U.S.A. and off to Tok and Valdez. We spent the next three days experiencing Alaska.

STRUGGLES AND STOPWATCH WARRIORS

Meanwhile, the TSD competition continued with teams growing more intense. Radio chatter on side channels debated minuscule mileage variations and GPS ping locations for the past few days.

Teams were split into classes. Amateurs managed oven timers and second-to-mile conversion charts. The pros wielded TSD Rally Computers that looked like garage-built amalgams of knobs, LEDs, and alarm clock displays.

We laughed at the contrast. We had decided to abstain from the competition before it even started in favor of the Grand Tour experience. In the FJ, we alternated between Dallas metal bands and Seattle indie emo covers during the 10-hour transit sections. My co-pilot, Dan, always had a bit of trivia to add to the playlist. “Did you know P-Diddy has to pay Sting a million dollars a year for the rest of his life?”

We tagged along on the TSD sections, assuming we would have dominated if we had tried. Dan, in his SpongeBob SquarePants pink dress shirt, called out mileage and landmarks. “Was that the cattle guard?”, “How many bridges have we crossed?” …and the recurring favorite “Where Are We?”

We felt bad when we’d pass true competitors, leaving them to fend with a thick fog of forest road dust and gravel, but we needed to cover ground.

On Day 9, we made a long excursion to Telegraph Creek. It was a speck of a town at the end of a 60-mile dirt road that traversed cliffside outcroppings connected by 20% grades. At the end, we surveyed Downtown Telegraph. There was a dilapidated former church, a closed bed-and-breakfast which still had cinnamon rolls taunting us behind locked glass doors, and a border collie that chased us over to the local museum until I threw steak jerky out the window to appease him. We couldn’t stay long since we had two hours of night driving still ahead of us. We were the last car back to Dease Lake. The photographer that had joined us in Telegraph Creek fell out of the cramped back seat, thankful to be off the road. We entered the dark lobby of the only hotel in town, where we were met with a competitive conversation, “I had 241 miles. What did you have?” A competitor was having a passionate debate with the Rally Master on TSD point calculations.

THE LONG ROAD BACK

As the highway names slowly changed, we knew the rally was ending. We navigated the Cassier, the Yellowhead, and the Caribou… all classic Canadian byways. By this point, we began to miss the frost heaves, swerving to dodge potholes, and dust clouds; however, we weren’t out of the woods yet.

The Audi enjoyed the road back to Whitehorse at a much more sedate pace. They had noticed a lack of power on any type of incline. One more pump change…back to the original…but no change. As they rolled into the Yukon Inn at close to midnight, they dug into their spare parts bin and replaced the fuel injection controller. Power had returned! Spare part hoarding for the win!

We went down the Cassier, through wildfire-damaged forests, on Day 10. The day ended at Dease Lake. The leisurely pace continued on Day 11 as we took a detour to Stewart, Alaska while on the Yellowhead Highway. The deviation was based on sightings of Grizzlies by team members. We stopped at Fish Creek just outside Hyder, AK. A park ranger shouted, “get on the boardwalk. There’s a bear!” We were skeptical this was a joke they played to stay busy and justify the entry fee, but the photographer assured us he saw a brown hairy rear end disappear into the brush. Weeks earlier Grizzlies were dining on salmon as tourists filled bleachers on a boardwalk just above the creek. Now we were left with rotting fish dotting the riverbed, giving off a pungent smell.

THE FINISH LINE

The last day was dominated by a five-hour segment of narrow dirt mountain roads, cliffs, dust clouds and one herd of cows blocking the roadway. Entering Williams Lake, the rally ended the way it began — in a hotel parking lot, but now with mud-spattered cars, bikes, and drivers who looked like they’d aged a decade and gained a lifetime of stories.

The Audi’s clutch whine finally took its toll. A mere two stoplights from the hotel, the clutch failed. Undaunted, the Audi was coaxed home sans clutch.

And us? Our FJ Cruiser sat outside, bug-splattered and dusty, but in one piece. The Toyota had survived. We didn’t win any TSD awards, but took home the only important award to us… the “Go Farther Award” and “Arctic Award.” Awards for those who were dumb enough to think 5,000 miles isn’t far enough. As we walked back to the hotel, we passed competitors drinking IPAs in front of the hotel, trading photos, and sharing contact details between new friends.

REFLECTIONS

Looking back, the Alcan 5000 felt far more like an expedition than a vacation. We met incredible people, discovered roads we never would have otherwise driven, and reset our definition of what qualifies as a “long day” behind the wheel. Wildfires and accidents closed routes along the way, spiking our anxiety, but the support staff and ever-reliable sweepers gave us a safety net we didn’t know we’d need.

It’s not exactly an easy sell: 13 straight days of twelve-hour drives, fuel bills that sting when gas runs $8 a gallon, 6,000 miles of wear on both car and driver, and the very real risk you’ll limp home without the car you started with. Who signs up for that?

And yet… the thought lingers. Experiencing it in winter has a certain pull. Besides, next year’s marathon leg to the Arctic Ocean is “only” eighteen hours—cut that in half with two drivers, and suddenly it doesn’t sound so crazy.